(Источник фото: http://www.apsnypress.info/.)

Об авторе

Лакоба Станислав Зосимович

(23.II.1953, Сухуми – 20.IX.2025, Гудаута)

Историк-кавказовед «новой волны», филолог, политик, литератор, проф. АГУ, лауреат Госпремии им. Д. И. Гулиа (1992), автор Лыхненского обращения (1989), гл. ред. и соавт. учебного пособия «История Абхазии» (1991, 1993). Окончил Сух. шк. № 19, ист.-филол. ф-т СГПИ (1976). Будучи школьником, увлекался археол. и ист., принимал участие в прибрежных раскопках и горных эксп. В течение ряда лет работал корр. газ. «Советская Абхазия» (1976–1978), затем учёным секр. Об-ва охраны пам. истории и культуры Абх. Находился в заочной аспирантуре под рук. проф. Г. А. Дзидзария. Защитил канд. дис. в г. Тб. на тему: «Абхазия в годы первой российской революции» (1985). В 1980–1999 работал в АБИЯЛИ им. Д. И. Гулиа (ныне – АбИГИ АНА) н. с., зав. отделом истории, в. н. с. В 2000 и 2004 в качестве приглашённого проф. занимался науч. работой в Центре славянских иссл. Ун-та Хоккайдо (Япония), где издал две книги: «Абхазия – де-факто или Грузия – де-юре?» (2001) и «Абхазия после двух империй. XIX–XXI вв. Очерки» (2004). Круг научн. интересов Л. – история и культура народов Кавк., мировая и региональная политика, вост. поэзия и лит-ра. Л. – автор более 100 монографий, книг, ст. и очерков, среди к-рых следует особо отметить «Очерки политической истории Абхазии», «Асланбей», «Ответ историкам из Тбилиси» и т. д. В этих работах содержится ряд принципиально новых оценок истории прошлого и настоящего Абх., основанных на док. материалах, ранее игнорировавшихся ввиду запрета или интерпретировавшихся односторонне. Л. также является автором поэтич. и публицист. произв. В его книге «Крылились дни в Сухум-Кале…» имеются главы, посв. А. Белому, О. Мандельштаму, В. Каменскому и многим др. известным поэтам и писателям, побывавшим в Абх. и писавшим о ней. Л. как политик принимал активное участие в НФА «Айдгылара», неоднократно выступал на съездах КГНК, полемизирует с груз. учеными по вопросам абх. истории и культуры, отстаивая самобытность абх. народа и его государственность. Во время груз.-абх. войны 1992–1993 являлся деп. ВС РА (1991–1996), в 1993–1994 – 1-м зам. Пред. ВС РА, а в 1994–1996 – 1-м вице-спикером Парламента РА. Участник Женевского процесса по урегулированию груз.-абх. конфликта под эгидой ООН при посредничестве России и участии ОБСЕ. С 1996 находился вне официальной политики из-за разногласий с руководством страны. В 1999 публично выступил против безальтернативных президентских выборов в Абх. В 2002–2003, в рамках Бергхофского центра (Германия) и неправительственной орг-ции «Ресурсы примирения» (Великобритания), являлся участником неформальных груз.-абх. встреч в Австрии и Германии в рамках Шляйнингского процесса. Одержал победу, выставляясь в качестве вице-президента в первых альтернативных выборах Президента Абх. (2004). В 2005–2009 и в 2011–2013 – секр. Совета Безопасности РА. 13.05.2013 выступил с офиц. заявлением перед деп. Парламента РА по вопросу законности выдачи абх. паспортов жителям Вост. регионов РА, являющихся гражданами Грузии. 28.10.2013 освобождён с должности секретаря Совбеза указом Президента РА А. З. Анкваб без объяснения причин. Л. – чл. СЖ СССР (с 1980) и СП Абх. Академик АМАН (2022). Председатель Фонда "Абхазское историческое общество" (с 2023).

Соч.: Боевики Абхазии в революции 1905–1907 годов. Сухуми, 1984; Абхазия в годы первой Российской революции.

Тб., 1985; Очерки политической истории Абхазии. Сухуми, 1990; Асланбей. Сухум, 1993; Ответ историкам из Тбилиси. Сухум, 2000; Абхазия – де-факто или Грузия – де-юре? Саппоро, 2001; Абхазия после двух империй. XIX–XXI вв. Саппоро, 2004; История Абхазии. Сухум, 2006, 2007 (соавт.); Крылились дни в Сухум-Кале... Сухуми, 1988 (2-е издание: Сухум, 2011); Избранное. (Стихи и рассказы). Сухум, 2011.

(О. Х. Бгажба, А. Э. Куправа / Абхазский биографический словарь. 2015) |

|

|

|

|

Stanislav Lakoba

An Abkhazian Prince on the Russian Throne?

Prince Georgii D. Shervashidze (Chachba)

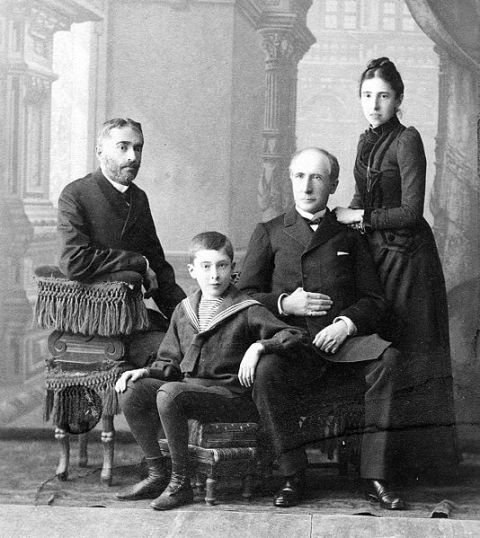

Prince Georgii D. Shervashidze with his family, his wife Maria Alexandrovna, their son Dmitrii and her father Baron Alexander Nicolai

The venerable Abkhazian princely family Shervashidze (Chachba) is renowned for having produced many famous personalities. The genealogy of the Shervashidze family is discussed in considerable detail in the fourth volume of the book “Noble Families of the Russian Empire” (Moscow, 1998).

One of the most brilliant representatives of the Abkhazian nobility is Georgii Dmitrievich Shervashidze (1847-1918), grandson of Hasan-bey (who spent the period 1821 – 1828 in political exile in Siberia) and the great-grandson of Keleshbey, the legendary ruler of Abkhazia who was killed in 1808. The prominent Abkhazian historian G.A. Dzidzaria gives a detailed account of Georgii Shervashidze in his book “The Formation of the Pre-Revolutionary Abkhazian Intelligentsia” (Sukhum, 1979, pp. 98-107). He records that Prince Shervashidze was orphaned at a young age and was brought up by the Governor of Kutaisi, General L.P. Kolyubakin, and his wife Aleksandra Aleksandrovna (nee Krizhanovskaya), a writer of children’s books.

As a child Georgii Shervashidze lived in St. Petersburg and abroad, and at the age of 18 he entered the law faculty of Moscow State University. During his second year of study, the 1866 uprising in Abkhazia took place. It was then that Georgii completed his student essay “Machiavelli: His Life and Works,” in which he noted specifically that Niccolo Machiavelli (1469-1527) considered any methods acceptable in politics, even those that spurn the norms of morality. Prince Georgii D. Shervashidze (Chachba)

Georgii Shervashidze received a first-class education, graduating from Moscow University in 1879. In 1877-1878 he took part in the Russian-Turkish war. In around 1879, he married the daughter of Baron A.P. Nikolai, Baroness Maria Aleksandrovna Nikolai, who was a niece of Nina Chavchavadze, wife of the Russian poet Aleksandr Griboyedov.

In 1883 he became the vice-governor of Tiflis. It was while serving in that capacity that in 1888 he several times in Novy Afon met Tsar Aleksandr III and his family and caught the attention of the Empress Maria Fyodorovna (the Danish Princess Dagmar). Less than a year later, Giorgii Shervashidze became governor of Tiflis, a post he occupied from 1889 – 1897. His friendship with Maria Fyodorovna continued after the death of Aleksandr III and the accession to the throne of her son, Nicholas II.

In the 1980s I discovered in Georgia’s Central State Historical Archive the personal file of Georgii Shervashidze with a detailed memorandum that mentions his son from his marriage with Baroness Nikolai-Shervashidze, Dmitrii Giorgievich.

The archive materials go a long way towards augmenting and clarifying many pieces of information concerning the dramatic fate of the two Shervashidzes, father and son. They include extensive correspondence dating from 1917-1918. According to these sources, on 13 November 1899 G.D. Shervashidze was transferred to St. Petersburg, where he served the Empress Maria Fyodorovna as Chief Chamberlain of the Imperial Court, and from 1905-1913 as head of chancellery. He and Maria Fyodorovna subsequently entered into a morganatic marriage. That marriage is a well-known fact, but the authors of the book “Noble Families of the Russian Empire” (Vol. 4, p.26) for some reason try to deny it. It was in that capacity that Shervashidze accompanied Maria Fyodorovna to England in 1911 at the invitation of King George V to attend the coronation celebrations.

The materials from the Tbilisi archives also reveal that after the abdication of Nicholas II, the Empress Maria Fyodorovna and Georgii Shervashidze tried several times to install on the Russian throne Shervashidze’s son, Dmitrii Georgievich Shervashidze (1880-1937). Those attempts failed, however. The elder Shervashidze was arrested in the Crimea and imprisoned in Yalta together with other prominent members of the imperial Court. The source gives the exact date of his death: he died in Yalta on 26 March 1918 and was buried in the crypt of the Aytodor church.

Georgii Shervashidze donated his unique library to the university that had opened in Tiflis (1918).

He was an extremely educated and cultured man who participated directly in the solution of a number of political issues in Tsarist Russia. It is possible that the lifting by the Tsarist government starting in the 1890s of some of the restrictive measures imposed on the Abkhazians, including the negating in 1907 of their “guilt,” were connected with the name of this influential figure at the imperial court.

Tsarist Prime Minister S. Yu. Witte writes about Shervashidze’s efforts in 1904 to avert the Russian-Japanese War. Witte, who was fiercely opposed to that war, sought Shervashidze’s help: “I consider it imperative to express my doubts and fears in the form of my full conviction to my great friend Prince Shervashidze, requesting him to convey my convictions to the Dowager Empress whom Prince Shervashidze serves. Prince Shervashidze fulfilled my request and I learned that the Dowager Empress spoke of this matter with the Tsar (Nicholas II), but His Highness said he sees no danger and there will not be a war” (S. Yu. Witte, Memoirs, Vol. 1, Berlin, 1922, p.353).

Georgii Shervashidze’s son Dmitrii Shervashidze was a man of vast ability and potential. It is of course a genuine sensation that during the tragic period of the revolution and its aftermath in 1917-1918 he was seen by influential members of the royal family as a possible claimant to the Russian throne. In the event of the restoration of autocracy, the Romanov dynasty might have been followed by the Shervashidze dynasty. Documentary evidence shows that in 1918 Dmitrii Shervashidze had an excellent chance of claiming the Russian throne with the support of Nicholas II and his father’s second wife, Maria Fyodorovna.

We know that Dmitrii Shervashidze graduated from the law faculty of St. Petersburg University. At the age of 21 he joined the staff of the Governor of Vilno, and at 34 he was named deputy governor of Stavropol. He married Yevgeniya Antonovna Terletskaya-Klimovich. In1916, when he was 36, he became deputy governor of Vitebsk, the post he still held when the 1917 revolution erupted. In a letter from Kiev Dmitrii Shervashidze informed his mother, Baroness Nikolaj, that he was arrested in Gatchina on 2 October 1918, then released by the Soviet government and ordered to leave the Soviet republic. He said he planned to travel to the Crimea and Sukhum, and that his wife and son Lev (Levan) were still in St. Petersburg.

At the end of 1918, Dmitrii Shervashidze arrived in Abkhazia where he lived on his estate in Kelasur, which had belonged to Hasan-bey. After the Bolsheviks came to power in Abkhazia, he was exiled in the 1920s to Irkutsk, where he worked as a lawyer until 1937. His son Levan and grandson Yurii lived in that Siberian city for many years.

Yurii Levanovich Shervashidze graduated from the history faculty of Irkutsk State University, and, according to Georgii Alekseevich Dzidzaria, he wrote a book entitled “Revolutionary Cuba,” published in Irkutsk in 1961.

It is possible that our information about the family of Georgii Dmitrievich Shervashidze will very soon be augmented by new archive materials or by an unexpected response from his descendants…

(Перепечатывается с сайта: http://abkhazworld.com/.)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|